ANKARA, Aug. 28 (Xinhua) -- Turkey's economic volatility and the currency tumble could affect living standard of millions of Syrian refugees in Turkey, as their vulnerable community would be among the first to suffer from a financial decline.

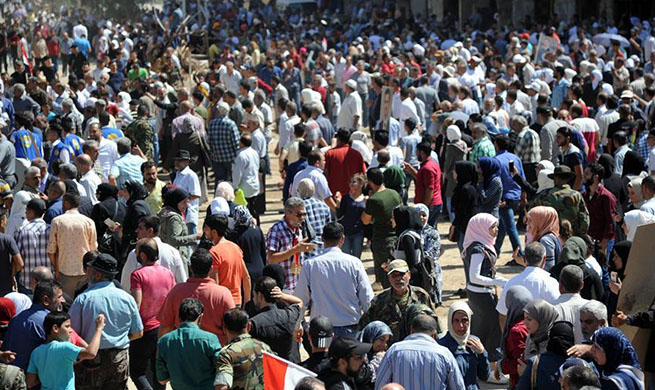

Over 3.5 million refugees are living in Turkey, more than any other country in the world, after having escaped the conflict that has continued for over seven years in neighboring Syria. The majority of these refugees live in cities and towns around Turkey, but less than 10 percent of them live in formal camps.

Meanwhile, there are at least half a million refugees from other parts of the Middle East and North Africa who also live in the country.

TURKEY'S HUGE EXPENDITURE ON REFUGEES

As of beginning of 2018, Turkey has spent 30 billion U.S. dollars for the refugees it hosts, according to a report from the Turkish parliament. The country comes in second after the United States on a list of most charitable countries in the world.

But many doubt if this could continue as Turkey's economy, the biggest of the Middle East, shows signs of worrying vulnerabilities amid an ongoing row with its NATO ally the United States over the detention of a U.S. pastor on charges of terrorism in western Turkey.

Both countries have imposed trade sanctions on each other and the U.S. President Donald Trump threatened with more severe measures as his Turkish counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdogan shows for his part no sign of backing down, branding his country's currency turmoil as an "economic attack" emanating from the United States.

"For the moment, we have not witnessed any budget cuts or project suspensions or delays," Metin Corabatir, an expert on refugee issues and chief of the Research Center on Asylum and Migration, said.

However, he went on, "if the economic stress continues and transforms into a crisis, we can expect that Syrian refugees will suffer from it because most of them work informally in Turkey and they can easily become jobless if their employers go bankrupt."

DECLINE OF PURCHASING POWER

The depreciation of Turkish lira has also impacted many refugees as they have seen their modest income crumble away, reducing dramatically their purchasing power like the same situation for the entire population of Turkey.

As part of an United Nations program, the Turkish Red Crescent Society delivers 120 liras (20 dollars) monthly per person by debit card to some 1.3 million Syrians. Many others work in the black market and are vehemently prone to Turkey's economic trouble.

"Life for the refugees would be even more difficult than it is right now if Turkey sinks deeper in economic trouble," emphasized Corabatir, who also pointed out that this situation would inexorably affect European countries once thousands of refugees hosted in Turkey leave for the wealthier European continent, causing a new wave of immigration, and surely a political crisis in the European Union.

Things are getting tighter by the day for Syrians working in big cities as their power of purchase declines because of regular price hikes.

"We are paid in lira like Turkish workers, but most of us don't have social security, thus no health or social insurance, and employers will get rid of us instantly when the company we work confront financial difficulties," said Mohammed, a 29-year old Syrian from Aleppo who works as a server in downtown Kizilay since 2014 and declined to give his surname.

"Food prices have risen recently because of the lira situation, but I still receive the same salary as the start of this year, so this is a real problem," added the worried Syrian man.

TURKEY-EU COOPERATION

Many of these migrants settled in Turkey because of the deal Ankara struck with the European Union in 2016. Under the deal, the EU agreed to give Turkey around 6.6 billion dollars to assist the refugees to permanently resettle there.

The only good news is that euro has become much more valuable because of the depreciation of the Turkish currency, and Turkey relies heavily on the funds for the refugees.

The refugee deal aimed to relieve Turkey's neighbor Greece of the burden of the migrant crisis and shut down the so-called Balkan route, which saw millions of refugees travel through Macedonia and Serbia to EU countries eventually.

Policymakers in Europe also wanted to disincentivize migrants from making the dangerous Aegean journey by boat from Turkey to Greece, where hundreds drowned on the way.

Turkey and observers fear of a new influx of refugees into Turkish territory, as Syrian leader Bashar Assad vows to recapture the opposition-held northwestern province of Idlib, where there are currently around 2.5 million displaced civilians, according to the UN.

"It is critical that Ankara should negotiate with its international partners over this humanitarian situation and also that the burden be shared," said Corabatir, fearing a catastrophic scenario if hundreds of thousands of new refugees flooded to the Turkish border to travel to Europe.

Erdogan will pay a state visit to Germany late September and the refugee issue should be one of the priorities on the agenda.

The EU is clearly worried that an economic meltdown in Turkey could spark a new migrant crisis on the continent. Turkey's woes resonate particularly in Germany, its biggest economic partner and home to a Turkish community of 3.5 million population.

The feeling in Ankara is the same since the start of the Syrian conflict: the international community should be more involved in the plight of the refugees that Turkey has been hosting with huge budget for several years.

"We have hosted millions of refugees since the start of the Syrian civil war seven years ago, but it is important that the international community also shares the burden as we are confronted with some currency difficulties which will be eventually resolved," a source at Erdogan's ruling Justice and Development Party told Xinhua.